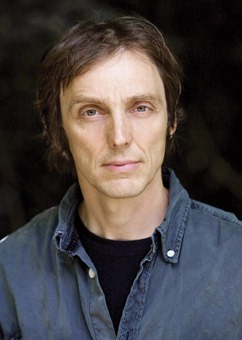

Philip Ball explores the patterns in Nature

By Christopher James

The stones of the Giant’s Causeway, the stripes of an Angelfish or the great spot on Jupiter all have a fascination for Philip Ball.

He has published many books on patterns of movement and formation of shapes in nature. A Chemist and physicist with an insatiable curiosity about symmetry and patterns in both the natural and man made world.

His work is complex but remains accessible because of an immediacy and connection with the everyday. He is always at great pains to deliver complex themes with examples and models relevant to us all.

“I try and think about very immediate things; the trees or clouds outside the window; things that have a real connection with people. Even the way that science intersects with art and broader culture. They all share a relationship with each other.”

“My real aim has always been to find areas of science that are cross disciplinary, areas where science intersects with broader culture.”

The question of disorder and determinism underpins his work and might even explain the shape of our cities or the layout of our undergrounds. Much of our culture, art and infrastructure may not be as self-determined as we would like to believe.

A degree in Chemistry from Oxford, a doctorate in Physics and an editor at Nature magazine for ten years begin to explain the breadth of the subject matter explored by his research.

His talk will barely scratch the surface of this fascinating subject but it will provide a clue about his expansive knowledge and a belief that nothing in the scientific arena can exist in isolation.

The talk will no doubt prove the point with the breadth of subject covered. Pinning him down to a favourite area of science was never going to be easy but if he absolutely had to choose one then what would it be?

“I have a bit of a mission for Chemistry. It is the science that has been most ignored and undervalued; neglected.” “It’s a difficult subject to popularise. It’s a real shame. In its broader sense it can help to explain the tangible world, the stuff around us. And of particular interest, the way in which patterns emerge from nature.”

There is no doubt that the public interest in science and the general level of knowledge has expanded in recent years. What changes has he witnessed?

“In the last twenty years there has been a real resurgence in the importance of scientific research across all fields; time, genetics, medical. You only have to look at the publicity surrounding the Large Hadron Collider to see the level of interest.”

He welcomes the renaissance but with some caveats for the medical sciences. “You only have to look at the MMR case and how distortions in popular media have led to a shortfall in vaccinations, the effects of which are only now being realised.”

The bulk of his work has taken place at an exciting time for science. The advent of computers and the power they bring has given scientists like Philip the opportunity to simulate much of the theory involved in their subjects for the very first time.

“One of the most striking things in this field of science is that a lot of the ideas we are looking at today were developed 100 years ago. There just wasn’t the computing power to explain or prove them. Although the rules developed for nature’s patterns are relatively simple, we are often talking about millions of separate components at work to realise these results. Computers are made for this kind of work.”

While passionate about his subject, it is illuminating that he cites the questions from the audience as the highlight of his talks. As a scientist, he was no doubt born curious but it is to his credit that the thoughts and ideas of others are still a major motivation.

The fact that he is even talking at this year’s event speaks volumes for the emergence of science as a popular subject.